How Elvis Costello Reinvented Himself on ‘King of America’

When Elvis Costello looked across the Atlantic to help inspire his 10th LP, he wound up anticipating a roots rock revolution. King of America, originally released on Feb. 21, 1986, proved to be a mosaic of nuanced, often opaque songs. It also showed Costello could lovingly riff on Americana royalty.

By late 1985, as Costello pondered how to follow 1984’s Goodbye Cruel World (a flop in his and his fans’ minds), the big, highly produced sound of American rock began to show cracks. Bruce Springsteen dominated the charts like never before with Born in the U.S.A. and its six Top 10 singles, but he would turn away from that magnificent bombast and radio-oriented approach with 1987’s Tunnel of Love. With American Fool, John Mellencamp had matured toward becoming the John Steinbeck of Heartland rock, and he would champion the roots renaissance with The Lonesome Jubilee. Bon Jovi and Motley Crue were minting money, but acoustic guitars, vocal harmonies and subtly would rebound in a few months thanks to Tracy Chapman, Indigo Girls, R.E.M. and even Tesla. U2 were about to “discover” America; Talking Heads were about to discover Americana.

During this period, Costello got divorced, wrote most of King of America and embarked on a solo tour alongside singer-songwriter T Bone Burnett, the soon-to-be producer behind the Americana rebirth. (Not only did he co-produce this album, but he also helmed everything from the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack to Robert Plant and Alison Krauss' Raising Sand). The two plotted a break from Costello's old sound, old band and old image.

When King of America appeared, it was created to “The Costello Show featuring Elvis Costello” in North America and “The Costello Show featuring the Attractions and Confederates” in the U.K. and Europe. But the Attractions only team up on one track ("Suit of Lights”), and the "Elvis Costello" stage name he'd used for a decade gets pushed aside — he's credited as nickname "Little Hands of Concrete" for performance, with Declan Patrick Aloysius MacManus (his real name if you strike the "Aloysius") for songwriting.

Costello had previously dabbled in Americana. Of course, he also dabbled in so much else: punk, pub rock, New Wave, ska, country, soul. But album 10 was striking for its relentless push away from his past. His name and backing band and electric anger feel distant in this wash of mandolins, dobros, accordions and brushed drums — so many brushes that the stick hits come off as positively ferocious.

Critics and super fans, who went wild for the LP, often call it personal or self-reflective, but Costello never seemed to hold much back before this. Instead the music smacks of shocking earnestness. The writer who could lean on sardonic sneers, ironic detachment and whirling fury finished his long ebb from those voices. Left behind was sincerity dressed up just right in twang and pickin’ — Costello and Burnett replaced the Attractions with American session aces dubbed “the Confederates,” which included Elvis Presely alumni (members of the TBC Band, who backed the other King from ‘69 to ‘77).

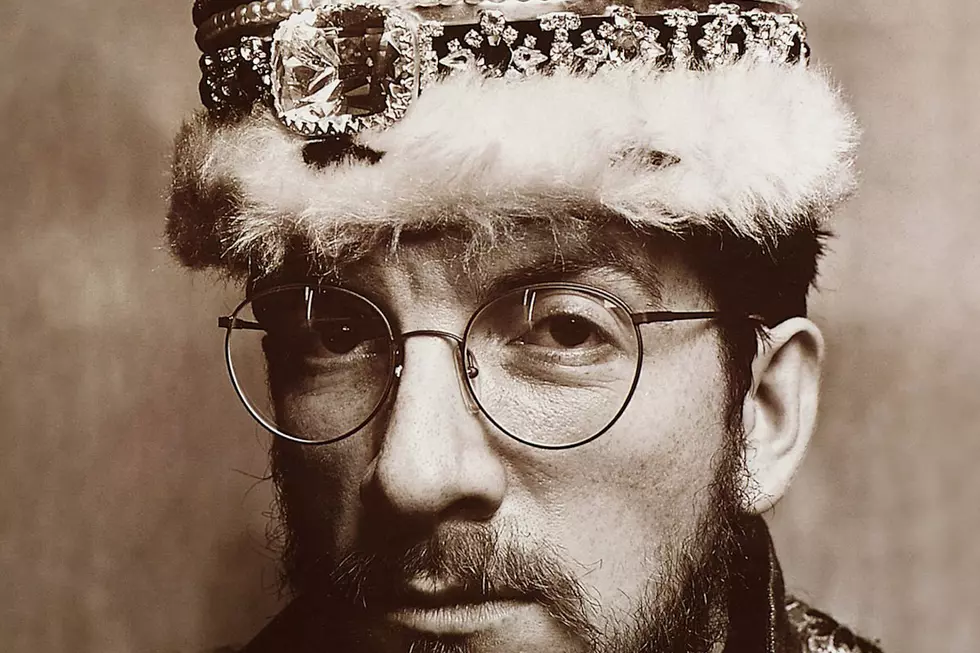

The LP opens with the woody thump of an upright bass, the lazy strumming of an acoustic guitar and Costello singing. “He thought he was the king of America / Where they pour Coca Cola just like vintage wine.” ("Brilliant Mistake" also features an insightful assessment of the country: “It was a fine idea at the time / Now it’s just a brilliant mistake.”) Definitively mid-tempo, it recalls something an Irish immigrant might croon on the docks in Boston, predicting the tone, speed and arrangement of Springsteen’s “Brilliant Disguise.” It defined the “new” Costello. The lyric that inspired the album title also influenced the LP cover photo, with the 31-year-old artist in a crown, looking like more introspective John Lennon than rave-up-ready Buddy Holly.

The set also includes doom-riddled folk rock (“Our Little Angel”) and blazing barnburners (“Glitter Gulch”). It finds the sonic overlap between Celtic and Appalachian traditions for a ballad about the battles of the working class (“Little Palaces”). It carves out space for a broken romance between Irish immigrants and G.I.s (“American Without Tears”). Costello covers old bluesmen, tries out lounge jazz, and closes the affair with a barbed, dense ballad about dignity, betrayal, estrangement and judgement: “Sleep of the Just” is the exact song the writer of “Allison” should have come up with a decade on.

His cult and the critics fell hard for the LP, but the record label and radio seemed befuddled and indifferent. In The Village Voice's annual Pazz & Jop critics poll, King of America finished at No. 2, but it peaked at No. 11 in the U.K. and only climbed to No. 39 in the States. In a bizarre, and perhaps ironic, twist, the label released his simmering, growling cover of Nina Simone's “Don't Let Me Be Misunderstood” as the first single, and it completely missed the Billboard Hot 100. The follow up, the rockabilly-meets-R&B jam “Lovable,” also failed to chart.

King of America is a dozen strange and wonderful things, none of them definitively. But it made one thing plain: Costello wasn’t the artist many thought he was. He would never again be the rock star that burst out of the ’70s British punk and pub rock scene. The album opened him up to everything.

Seriously. Ignoring hardcore and metal, he has spent the past 35 years basically doing it all: working with the Brodsky Quartet and Burt Bacharach, Paul McCartney and the Roots, writing a ballet score, dueting with mezzo-soprano Anne Sofie von Otter, taking opera and orchestral music seriously, and, often, returning to the earthy aesthetic of King of America.